(The lyrics from PJ Harvey's songs are copyright PJ Harvey. I took them off a lyrics site and hope they are entirely accurate.)

July 1st, 2011, we took the ferry from Dover to Calais and drove south for about an hour and half to the town of Arras for the Main Square Festival, mainly to see PJ Harvey. She'd just released her eighth studio album, Let England Shake. It's a beautiful collection of songs whose predominant themes are war, destruction and the resulting loss. (Move your mouse over the lyrics to clear the background.)

Field of Flax

The Glorious Land, by PJ Harvey

How is our glorious country ploughed?

Not by iron ploughs.

Our land is ploughed by tanks and feet.

Feet

Marching

Oh, America

Oh, England

How is our glorious country sown?

Not with wheat and corn.

How is our glorious land bestowed?

What is the glorious fruit of our land?

Its fruit is deformed children.

What is the glorious fruit of our land?

Its fruit is orphaned children.

Arras is near the Somme and was the scene of a bloody battle during World War One, from 9 April to 16 May 1917. In less than one month, there were about a quarter of a million casualties (dead, missing, and wounded), equal numbers on both sides. The Commonwealth troops alone were losing two thousand men a day. As you drive south through Calais Nord towards Picardy and the Somme, it seems that you pass a military graveyard every mile or so. Some of them are 'small', with a thousand graves; some of them, like Vimy, are huge, with over ten thousand graves. The sense of loss, early death, and destruction is pervasive and ever-present. You cannot shake it off and are continually reminded of it.

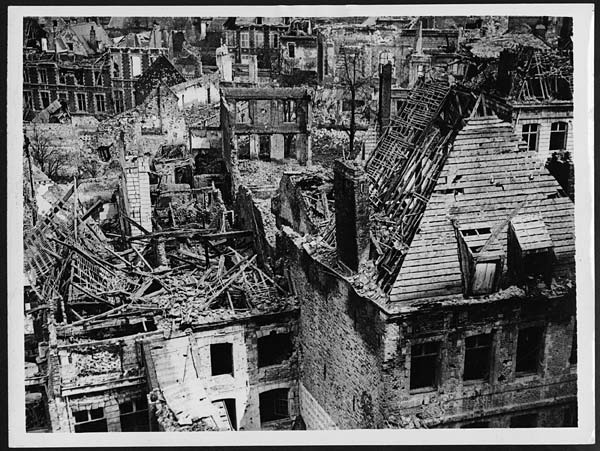

The town of Arras was under continual bombardment and was largely destroyed. Arras was originally a Flemish city and much of the architecture is typically Flemish, like you would find in Antwerp, Gent, or Amsterdam.

Arras 1917

Arras 2011

On our second day there, we took a wrong turn while trying to find a more interesting route from our campsite to Arras and ended up driving down narrow tracks through the fields pictured above. Wide fields of flax and wheat, sparkling in the sun, interwoven with wild flowers, poppies and chamomile, covering the battlefields and the bones of the dead.

We stopped to look at one of the graveyards and were the only people there, among the perfectly-maintained lawns, flower-beds, and the uncountable rows of clean gravestones. So many of them were inscribed 'A Soldier of the Great War'.

Unknown Graveyard of the Great War

Unknown Soldiers of the Great War

As we were leaving that graveyard, we met a retired couple from the West Country who were on their third or fourth visit to the area. They'd visited all the main memorials and told us about the large, breathtaking ones at places like Vimy, Thiepval, and Monchy le Preux. They also told us about the War Graves Commission's website where you can type in the name of any Commonwealth soldier and locate their grave.

I remember hearing that my Jersey grandfather, Phil Potier, had lost a brother in the war so when we returned to the campsite I used my phone and their WiFi connection to look him up. There was only one family called Potier on Jersey, and this is what I found:

War Graves Search

We found Bouchoir on the map and it turned out to be only an hour's drive south of our campsite, so we decided to go down there on the Monday after the festival. The festival was open air, but in the confines of a Napoleonic fort, and there were about 25,000 people squeezed in there. It was the hottest day of the weekend, about 29 degrees, and the security guards took the lids of our water bottles away and binned them on the way in, meaning we couldn't refill them. When I questioned the logic behind this I was told, 'It is the law - all across Europe!' Really?! Apparently, it's supposed to stop you launching full bottles at the bands you have come to see. Inside they were selling bottles of water with lids on and the dirt ground of the old fort was strewn with fist-sized rocks. Nobody was picking them up.

That kind of low-level stupidty, implemented by officious and arrogant-behaving minor officials really incenses me. Doesn't anybody in the food chain question anything? At the Hop Farm Festival in Kent, last year, it was sweltering and they were making you tip away your bottled water when you entered the arena. You could keep the bottle and refill it inside but there was a 40-minute queue at the three stand-pipes. Their rationale was commercial: they didn't want people to bring their own alcohol in and wanted to force them to buy from the official places. Same dumb stupidity.

We got near the front for PJ Harvey. She played a lot of Let England Shake, which was fantastic. The band were hot, hot, hot in a studied, intelligent way. A lot of musical variety from three or four musicians. Some of the songs seemed shorter than on the album, but I guess she had to play some of her back-catalogue as well, since a lot of the people around us only got excited when she got into that.

The Words That Maketh Murder, by PJ Harvey

I've seen and done things I want to forget;

I've seen soldiers fall like lumps of meat,

Blown and shot out beyond belief.

Arms and legs were in the trees.

I've seen and done things I want to forget;

coming from an unearthly place,

Longing to see a woman's face,

Instead of the words that gather pace,

The words that maketh murder.

These, these, these are the words—

The words that maketh murder.

These, these, these are the words—

The words that maketh murder.

These, these, these are the words—

Murder...

I've seen and done things I want to forget;

I've seen a corporal whose nerves were shot

Climbing behind the fierce, gone sun,

I've seen flies swarming everyone,

Soldiers fell like lumps of meat.

These are the words, the words are these.

Death lingering, stunk,

Flies swarming everyone.

Over the whole summit peak,

Flesh quivering in the heat.

This was something else again.

I fear it cannot be explained.

The words that make, the words that maketh

Murder.

What if I take my problem to the United Nations?

Other stand-out acts for me were Portishead, who had a great video show and an amazing amount of white-noise guitar, scratching and synth, with Beth Gibbons singing in an aching, blues manner like Janis Joplin. Coldplay headlined and were beautiful and warm, with a great light show, fireworks, balloons, and explosions of glitter coming from somewhere I'm not sure of. Their music was good too.

When we left the festival, they led us out of a side entrance, not the one where we'd deliberately parked close to. We exited into a different part of town and wandered around the back streets of Arras at 2 a.m. trying to remember street names. Eventually, Kate remembered the name and we used my phone, again, and Google maps told us how lost we were. In the days before gadgets, we would have just asked a stranger and had 'an encounter'.

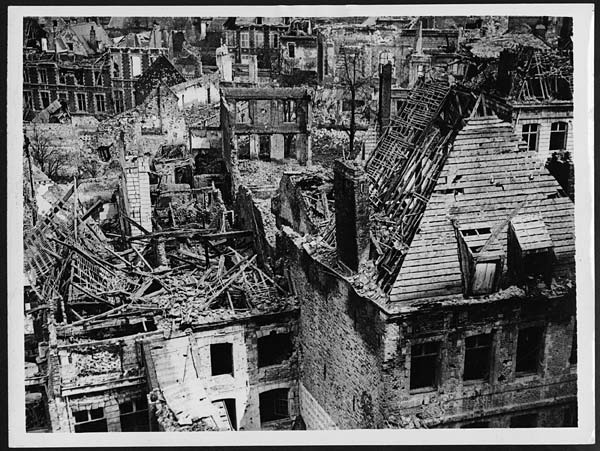

The point of all this. On the Monday we left the campsite and drove south, listening to Let England Shake, seeing all the war memorials and thinking of the millions of young men who were led into hell and suffered torments before dying in terror. They had to advance over the bodies of their fallen comrades, some of them still alive but drowning in shell craters that filled with water, tangled up in the barbed-wire, unable to free themselves. How would it feel to put your boot into the face of your fallen comrade in order to advance into machine gun fire, shell-bursts, and mustard gas?

Dead British bodies after the earlier battle of Arras, spring 1915

We turned off the main road and headed for the little village of Bouchoir, looking for the British Cemetery where Herbert Potier was buried. The rural roads of northern France seem to be permanently empty. Occasionally you pass a car coming in the other direction but mostly it is just you, slowing down to drive through indistinguishable villages, each with its boulangerie, pharmacie, charcuterie, tabacs, one bar, and a cross by the roadside. In that part of France there is always also a monument to the men of the village who gave their lives for their country.

The turning for the cemetery was before the village, coming from the east, and we almost missed it. It doesn't look like a road, just a track that runs parallel to the road behind a hedge for about 100 metres and then turns into the fields. It was a hot, sunny day with a strong breeze that stroked the wheat in waves, like a hidden hand. In that flat landscape the fields stretch almost to the horizon – about the closest thing you'll get to Montana, I suppose, in this part of the world. We got out of the car and took in the silence, which was eerie. It was something to do with the fact that we were on a mission of remembrance, seeking out the grave of someone I never knew, but who could have been my grandfather. He left his home and gave his life. I thought of his mother, saying goodbye, and him, in France, knowing he wasn't ever going to go home. Never going to live his life.

His Resting Place

We found his grave and took a few photos of it and me next to it, to show my family. As far as I know, I'm the first of his relatives to discover his grave, since it is only in the last twenty years that the War Graves Commission data has been easy to access - and mostly since it went online.

I don't believe in any form of life after death but I do believe in a spirit that commands the attention of the living and that our memories of the dead are a powerful component of that, one that affects us and influences our behaviour. And I believe that we have a duty to remember them and recognize their contribution - not just the war dead, but everyone who lived on this earth and suffered, and who put their own spirits into making the world we live in.

So while we were in that perfectly still place amongst all those graves, I was overcome with the sensation that all those young men were still lying there below the ground, in the middle of nowhere waiting for the rest of us, who are alive now, to come and say goodbye to them, to acknowledge their suffering and how they lost their lives.

As I walked around the graveyard I could see them as they were when they were alive - laughing, smiling, young and hopeful, and thought about how they were cut down. I wanted to say Sorry to them and let them know that we understood their suffering so that they could move on. It was like we had a great debt to them that still hadn't been paid.

All of those graveyards have a little safe-box built into the wall in which you can find the plan of the graveyard with the names of those buried there and a visitors book. We opened the visitors book and read through the comments and it was too moving to continue. The one that finally broke me up was written in a weak, spidery, aged hand. The comment said: 'Found you at last, dad. rest in peace.' So this was someone in their eighties or nineties who had finally found the grave of the father they'd never known.

The book of remembrance

I burst into tears and couldn't stop sobbing. I wanted to write something in the book but was crying too much. It took about ten minutes to pass and a lot of things went through my mind that I only understood in the hours and weeks that followed. Eventually, my feelings came back to normal and I wrote something unemotional and plain.

We got in the car and drove away but my thoughts were still filled with tears and remembrance. I thought of how peaceful, beautiful and rural Jersey was at the turn of the 20th century when Herbert was born and what a violent contrast it was for him to be taken to hell. How he must have wished to have been back at home. Not just him - all of the young men from all around the world, especially the Indians, African, and Chinese from the Commonwealth who knew and cared nothing about the political machinations of the ruling families of Europe.

While we were in the graveyard I was thinking about the Germans who died, and weren't remembered. This was not World War II, where there was a strong moral reason to fight Hitler. This was a war in which the stupidity of our leaders was equal and the men of all countries were basically sent into an abattoir to be killed en masse with industrial methods. There were as many German deaths as French and Commonwealth ones: presumably their bones are lying down there forgotten.

German soldiers rescuing a French soldier

I saw images of my own children, and now, my grandchildren. I remembered the words of the buddha: 'Birth is suffering'. There's no avoidance of it. I thought of the battlefields, the words of Krishna to Arjuna:

So Krishna, as when he admonished Arjuna

On the field of battle.

Not fare well,

But fare forward, voyagers.

From 'The Dry Salvages', by TS Eliot

And I thought of the continual wars around the world - the people who make the arms and sell them to the poorest people so that they can kill each other. Like in Somalia, now, where the slaughter opens the door to famine. Something came back to me from long ago, when I was a teenager, still living in Jersey. My cousin, an electrician was doing some work on the house of a tax-exile millionaire or billionaire. One day he asked him how he'd made his money. The guy gave a wicked, knowing grin and said: "I do a lot of work in Africa, selling cutlery to the natives." Fuck you! I now understand what that meant and what your complicit grin meant: they can kill themselves and I make lots of money, which I avoid paying taxes on by moving to Jersey. There's still a lot of it around.

When I was very young and I read or heard about the supposed 'Dark Ages'—a time of plague, disease, early death, dungeons, cruelty, ingenious weapons of torture—I used to feel so lucky to be living when I was, and ponder how it was that people then could not see how terrible things were and why they did nothing about it.

Now that I know what our own world is like – that we still have torture, stupid wars, famine, and avoidable disease (just that it is not on my doorstep) –, I like to project forward a hundred or two hundred years, imagining that the human race had developed a compassionate intelligence and put behind them the terrible injustices and cruelty of our time.

And I wonder what it is about how we live now that would make them shudder. My best guesses are:

A robin redbreast in a cage Puts all heaven in a rage. A dove-house filled with doves and pigeons Shudders hell through all its regions. A dog starved at his master's gate Predicts the ruin of the state. A horse misused upon the road Calls to heaven for human blood. Each outcry of the hunted hare A fibre from the brain does tear. A skylark wounded in the wing, A cherubim does cease to sing. The game-cock clipped and armed for fight Does the rising sun affright. Every wolf's and lion's howl Raises from hell a human soul. The wild deer wandering here and there Keeps the human soul from care. The lamb misused breeds public strife, And yet forgives the butcher's knife. The bat that flits at close of eve Has left the brain that won't believe. The owl that calls upon the night Speaks the unbeliever's fright. He who shall hurt the little wren Shall never be beloved by men.

From 'Auguries of Innocence', by William Blake

If it's true for the robin redbreast and the little wren, it's no less true for men and women.

We have a duty as citizens to be aware of these injustices and outrages perpetrated in our name by powerful governments and corporations. Knowing about them, we also have a duty to try and stop them by any means we can, especially by exposing and pursuing them - not letting them get away with it like they did in World War One.

After we left the graveyard, we headed back towards Calais and England. We'd made a picnic and stopped at an aire de picnic beneath some trees. It was so peaceful and enjoyable that we almost missed the ferry and had to drive full-speed to get there on time. As I drove north, I was almost sickened by the images of death all around me and felt sorry for that whole region of France where so much destruction and death had occurred, and for the fact that it has to be remembered forever.

It would be good if there could be some kind of ceremony or ritual where the descendants of the soldiers who died went to that area and pledged to live in peace. We could say goodbye to them and release their spirits from that haunted place. I think then that those men who died so unnecessarily would forgive us and allow us to forget their graves, so that life can move on. So that our children can start again and play where they died. I might be wrong and it might offend some people, but I think that if we did something positive as a result of their deaths, those dead men would forget us and disappear. They wouldn't hold it against us.

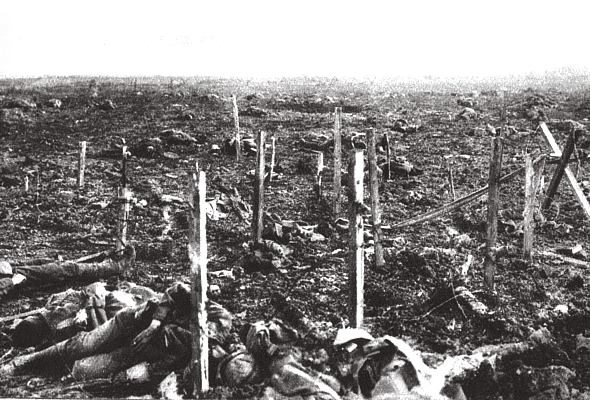

Life during peacetime

When we were back in England, 'beautiful England', I rang my mother from a service station and told her about finding Herbert's grave. She told me a story, which may be apocryphal. My great-grandmother, after losing her first son in the war, told her other two sons, who were of fighting age, to leave for Canada. She sewed gold coins into their clothes and sent them away and never saw them again. It has the qualities of a fairy tale to me, but maybe there is some truth in it. I would do anything to stop my children being killed in a stupid war being fought for ignominious ends - a war in which the perpetrators stay far from the horrors of the battlefields and send other people's children to die for them. I know they went to Canada because I met one of them, Jack, many years later, when my wife was expecting our first child. Jack married a native American woman, a Huron. She later sent my son a poncho she'd knitted for him.

The Last Living Rose, by PJ Harvey

Goddamn' Europeans!

Take me back to beautiful England

and the grey, damp filthiness of ages,

fog rolling down behind the mountains,

and on the graveyards, and dead sea-captains.

Let me walk through the stinking alleys

to the music of drunken beatings,

past the Thames River, glistening like gold

hastily sold for nothing.

Let me watch night fall on the river,

the moon rise up and turn to silver,

the sky move,

the ocean shimmer,

the hedge shake,

the last living rose quiver.

It's several weeks later. I wanted to write this up, partly so that my ancestor who died is acknowledged. He'll never be forgotten now, and he can move on too. Like I said, I don't believe in a soul that lives after death, but I believe that what we call mind lives forever. Everything you do or say influences everyone else. The actions you take have significance. When someone does a wrong, that wrong lives on somewhere in the human race until it has been addressed. The First World War was a mighty wrong that still resonates in us. The best that we can do to recompense those young men who died is to live in peace, and to have compassion for everyone who suffers. To not stand idly by when we see injustice.

When challenged about not observing religious rituals by attending a funeral, Jesus said, 'Let the dead bury their own dead'. He said some harsh things, but they were mostly strategic. He was dealing with the powers that be, an empire that wanted to crush him. He was up against it. He knew that his accusers weren't thinking of the person being buried when they said that: they were thinking of how they could use that as a means of intimidating him.

When Muhammad Ali was conscripted to fight in Vietnam, he refused, saying: 'I'm not travelling half way round the world to kill someone I don't know because his skin is yellow. No Vietcong ever called me nigger.'

Toa Te Ching

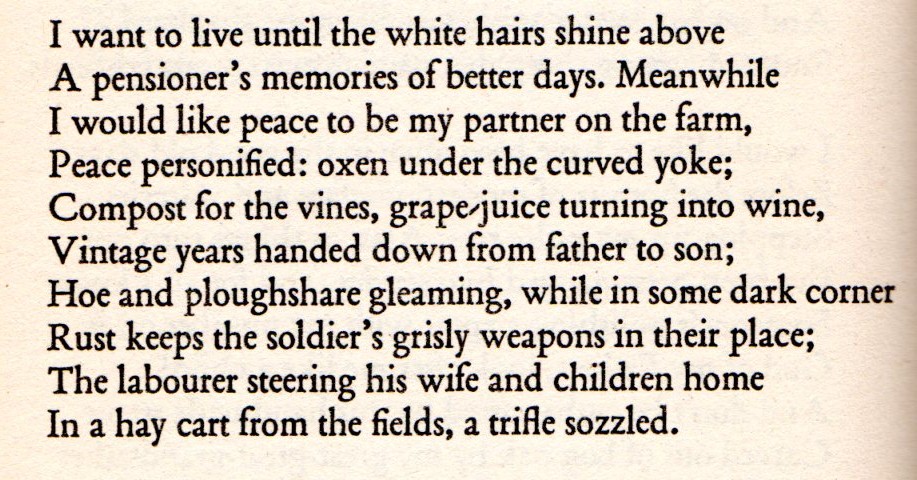

And this poem by Michael Longley, 'Peace', which is an adaptation of 'Peace and War', by the Latin poet Tibullus.

Michael Longley, 'Peace' - stanza 5

We did some digging into the family tree. Herbert Winter Potier was not my grandfather's brother. He was probably his cousin, not that it matters. He could have been anyone, even someone not related to me. It's about the journey, not about what you perceive as your destination. Fare forward, voyagers!

Rob Kent, July 23rd 2011

Click to toggle notes and references